Last week, the Italian government issued a decree that changes the citizenship rules for the Italian diaspora. They have “slammed the door!” on people who seek citizenship through a ten-times-photocopied birth certificate of their great-great grandfather Pasquale. No more EU passports for them!

Effective immediately: “Fewer people of Italian descent will now be able to obtain citizenship after the government narrowed eligibility only to those with Italian parents or grandparents,” The New York Times writes. And further, to claim citizenship, your parent or grandparent cannot have been naturalized as an American (or Canadian, Argentine, etc) before the birth of the applicant. Plus, the new law will require proficiency in the Italian language, and requires certain applicants to have lived for two consecutive years in Italy.

Good! I say. It’s about time.

Until last week, anyone and their grandmother could seek Italian citizenship through jure sanguinis – or citizenship by bloodline. If they could document an ancestor who was alive after Italian unification in 1861, they were in. As a result, every Tom, Dick, and Anthony in Long Island and New Jersey with time and money on their hands has can go through the rigamarole, as my mother would say, of procuring an Italian passport to lord over their friends and neighbors over plates of Chicken Parm. Whether they would ever use the passport was beside the point. And the process, including lawyers, finding and translating documents, and on and on, from what I have heard from people who have done it, can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

To me, this is obnoxious: the quest for Italian citizenship has become a hobby, a boondoggle, and a misplaced method of connecting to family and understanding culture. The Dual US-Italian Citizenship Facebook group is an unending discussion of the legal and bureaucratic ins-and-outs of the literally byzantine process people must go through to connect themselves, on paper, to Italian-born ancestors, and then eventually register themselves as citizens of some little town that their family left ages ago, to which many have never been. Few of these applicants even speak Italian, meaning much of the slog is farmed out to a cottage industry of lawyers and others who can negotiate the language and system for them. And the wait times for Consulate appointments to seal the deal are comically long: more than a year.

The Facebook posts are, per tradition, headed with jargon like “Miami JS 1948 GGGF GGM GF F Me.” Allow me to translate: through the Miami Consulate, this person is claiming jure sanguinis citizenship, and is a “1948 Case” (ie, someone claiming ancestry through a female ancestor born before 1948, when ancestry could only be passed down through the male line blah blah blah). This person’s bloodline goes through his great-great-great grandfather and down. Can you, off the top of your head, name your 3X-great grandfather?

I am sorry but this is nonsense. It’s an all-consuming distraction that can keep a whole family occupied for years. Maybe it’s not the right forum, but aside from the rare “when I went to my grandfather’s village, my heart felt at home” line, there is hardly a reason given in the Facebook group for wanting the citizenship other than posting a gloating photo of you and a burgundy passport.

And while many of these people might know a lot about Italian-American culture, what do they know about Italy today? Its pop culture, its music, its politics, any of it? I’ll make this easy! Here’s a citizenship test Italy can use, not for the people seeking actual asylum, but for the Long Island people named Marie who went on a cruise once. Here it is:

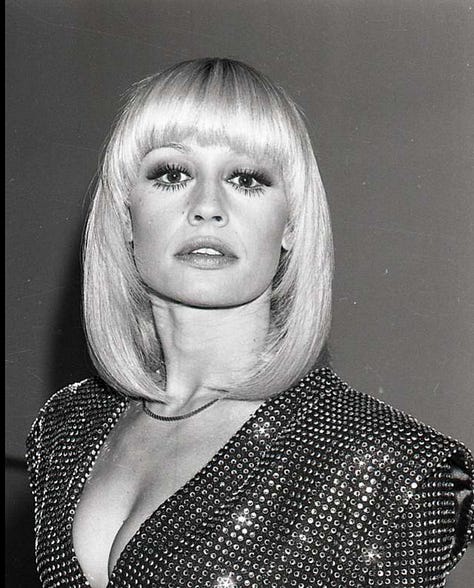

Which one of these people is Raffaela Carrà?

If you don’t know and love legendary Italian singer, dancer, presenter, and icon La Carrà, then what are you even doing?

There certainly are many people seeking citizenship who speak the language, have real connections to Italy, and have other very good reasons for wanting Italian citizenship beyond some vague sense of a foreign identity that makes you seem artificially more interesting to people you run into at Pathmark. But to the majority of applicants, I say if you want to connect with your Italian heritage, then connect with the actual heritage, not its paperwork.

Because my mother was born in Italy, people ask me sometimes if I have applied for citizenship. I have not. I am ineligible. It’s a little annoying that I have had to bear all the aggravation of an Italian mother and Italian grandparents and be yelled in Italian so much and am still not eligible for citizenship.

My mother and her family left Italy in 1956 under the Refugee Relief Act of 1953. They became US citizens in 1961. Since my mother was a US, not Italian, citizen when I was born, the chain of the bloodline, according to the Italian government, is broken. I am an American, born to an American. I could have also (but no longer) potentially applied through my father’s side of the family, because I suspect my paternal-line great grandfather did not become naturalized when he moved to the US, and was an Italian citizen at the time of my grandfather’s birth in Brooklyn.

I have never wanted to pursue this quest, to find the documents, get the apostille, and wait a year for a Consulate appointment. Why? I think of something my grandfather said to me when I moved to Park Slope, in Brooklyn, after college: “I spent my whole life trying to get out of Brooklyn,” he said, “and then you move back.” He also said don’t go past Seventh Avenue, and I did listen to that. It was the 1990s, when Hipster Disneyland didn’t push quite so far into the borough and Fourth Avenue was still pretty scary.

Why do we want to go back? What do we think we are reclaiming with this citizenship? I imagine what my mother’s life likely would have been like had she and her family stayed in Mongrassano in the 1950s, and beyond. Electricity and running water were scarce. Malaria was still endemic, and still treated largely by traditional medicine. She would not have been educated past middle school. There was little work, for anyone. And my grandfather, if his family had stayed in Naples? For him, the Fascist army; a difficult, back-breaking job, perhaps overseas; and certainly no college, as he was able to go to City College in New York, like so many new Americans.

It’s a profound to think that we find ourselves at a turning point in our family history when the chain has just been broken: for seemingly countless generations our ancestors all lived in one place, and then a few people crossed an ocean, and everything changed. But no family belongs to one place for very long anyway, in the grand scheme of things. All people are migrants. “Migrant” has a bad tinge to it now in the US, but that bias fails to recognize that this is our natural state. People shift from place to place, and while it seems to take ages for large shifts to happen, it comes down to one family, in one year, making a leap from one place to another, for any reason: war, poverty, opportunity, love, and its always frightening. The legal chain breaks, but the family line carries on.

I think of the Roman Empire (who doesn’t?) and how they defined citizenship. Being Roman, and exercising the rights of a Roman citizen, had little to do with blood. My favorite Roman historian and TV star, Mary Beard, points out that from its mythical beginnings, “Rome saw itself as a city of asylum seekers.”

Rome’s first king Romulus attracted citizens to the city he founded on the Palatine by calling it an asylum. Later, in its non-mythical history, the emperor Caracalla gave citizenship to 30 million (unslaved) inhabitants at once. Citizenship was a mechanism for incorporating outsiders, rather than excluding them, Beard says. But this agreement came with both rights (a Roman citizen could not be crucified, for instance), and also the responsibility for putting boots on the ground, and building the Empire’s military power. American citizenship, for all of its challenges, is similar: it is hard-won by immigrants from all over the world. Citizenship is serious; it demands commitment and sacrifice along with its benefits; it’s not just a piece of paper.

Why then, would the Italian government want to continue to spend money and time on expensive bureaucracy (Italy already has plenty of that) to grant citizenship to people who will never participate as citizens? Will never pay taxes, or join the army, or vote, and who are already active citizens of another country? From the Times article:

Alberto Teso, the mayor of San Donà di Piave, a city near Venice, told the public broadcaster RAI in February that half of his staff worked full-time on citizenship applications for people…who “will never set foot in our city.”

I’ve been to San Donà. I’m still never getting citizenship.

Some people may buy property and live in Italy someday (usually when they retire, from what I can see on the Facebook group). It is ironic, though, that the people whose families left Italy to escape poverty generations ago now want to return. Maybe they will buy one of those one-Euro homes for sale in the South, in one of the sparsely-populated villages that the families of these applicants left in the first place. See where that gets you.

The number of Italian citizens abroad has grown by 40 percent in the past decade, the Times reports. These applications are jamming up the courts and do nothing to solve Italy’s problems with its decreasing, aging population, or improve its policies toward the migrants who arrive on Italy’s beaches seeking asylum from war, poverty, and disaster in the thousands. Italy does not offer jus soli, or birthright citizenship, so Italian-born children of immigrants must currently wait until they are 18 to apply for citizenship, and find themselves in limbo until then.

I loved going to visit my mother’s hometown, Mongrassano, in Calabria. It has a sad, ragged beauty about it, and it does hold a place in my heart, but I also know, in my heart, that it is not my home. I will visit, and I will learn more about it, and keep what I can of its culture with me here, alongside my American, and Italian-American, ways. I will continue to speak the language, but my mother tongue, the one that my Italian mother taught me, is English.

And also I don’t think my mother knew who Raffaela Carrà was, by the way, because after she left Italy she became was an American, and never really wanted to look back. I only know La Carrà because I found her in Italy myself, and when you’re there for a while, you can’t miss her. She was amazing.

You don’t have to dance with the one who brought you. You don’t have to choose the US because your ancestors made that choice. You can choose to migrate, as humans have done all over the earth since prehistory. But to go through the theatrics of migration to then reject the country whose citizenship you sought, just to stay in place, and brag to your friends? “Knock it off,” my mother would have said, and that’s what I say too.

Such an interesting post, and of course I have thoughts. 😉 I have always wanted to get Italian citizenship, and thought it was strange that my elder cousins could but I cannot. My mother was born after her parents were naturalized in Canada, to help avoid deportation in WW2. It is hard to argue against requirements around voting and taxes, and I think you make a great point about the responsibility citizenship entails. I can’t help feeling that sense of loss described in the article, though. The government doesn’t see me as Italian, and yet when I was in Cosenza, so many people commented on how I looked local to Calabria. So I must carry the Italian nose but not the passport, and somehow that must be enough.

ALSO....there is such an incredible resemblance between you and the beautiful people in the photo you posted! xo